Stage Lighting 101 — Everything You Need to Know

Stage lighting is an art form. It’s used to illuminate a performance venue and make an impact on an event, giving visual direction and shaping the environment. There’s a lot to learn about stage lighting. In this post, we’ll cover some of the foundations of stage lighting that are helpful for anyone in the live performance space to understand.

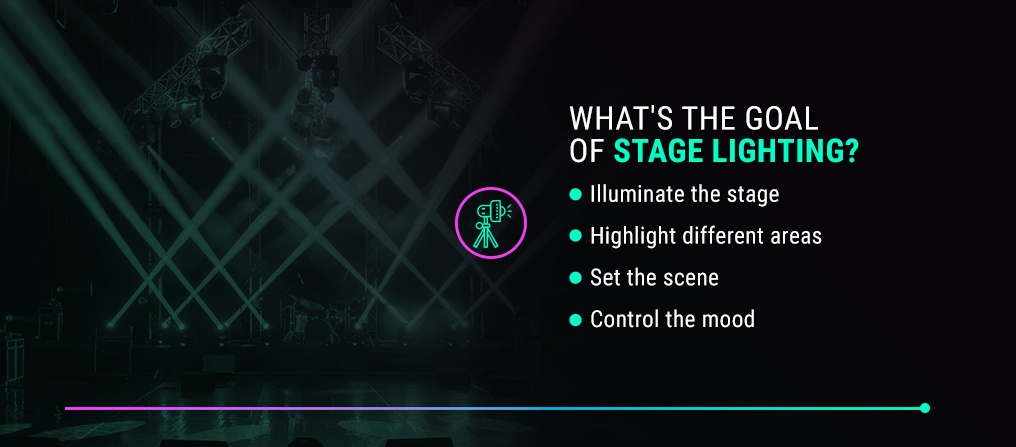

WHAT’S THE GOAL OF STAGE LIGHTING?

The goal of stage lighting isn’t limited to one objective. Stage lighting can help you capture the audience’s attention and enhance a stage production in a number of ways. The right stage lighting can:

Illuminate the stage: The most basic objective for stage lighting is to illuminate the performers, sets and props so the audience can clearly see everything they’re meant to see onstage. Inadequate lighting can take away from a production. For example, dim light will make it harder for actors’ facial expressions to come through — even to audience members seated close to the stage. Illumination is also important for the people onstage, so they can see where they’re going and see the other dancers, actors or musicians.

Highlight different areas: Stage lighting can also help you direct audience members’ eyes where they should go. In the most dramatic instances, the majority of a stage may be dark with just one spotlight shining on a focal point. In many other instances, the lighting engineer can start with a wash, which covers a wide area and acts as a base layer of light. Then, they can use accenting to guide the audience’s attention to a particular area, like a speaker in the foreground.

Set the scene: Lighting can also help you create the visual you want in a scene. In some instances, this means creating optical illusions with lights. You may use a moving light to make it appear as though the sun is rising, or make the stage go dark as an actor flips a prop light switch in a room. You can also use backlit scrims to create the illusion of a starry night, a sunny day or even a fire.

Control the mood: Stage lighting can also have a major effect on the mood. The idea is to match the lighting to the content of the show to encourage the right emotions in the audience. This could mean a soft, warm glow for a happy scene in a play or dim, cool hues for a sad ballad during a concert. Certain colors are associated with different moods. For example, blue is often associated with sadness, and red is associated with intense feelings, like love or aggression.

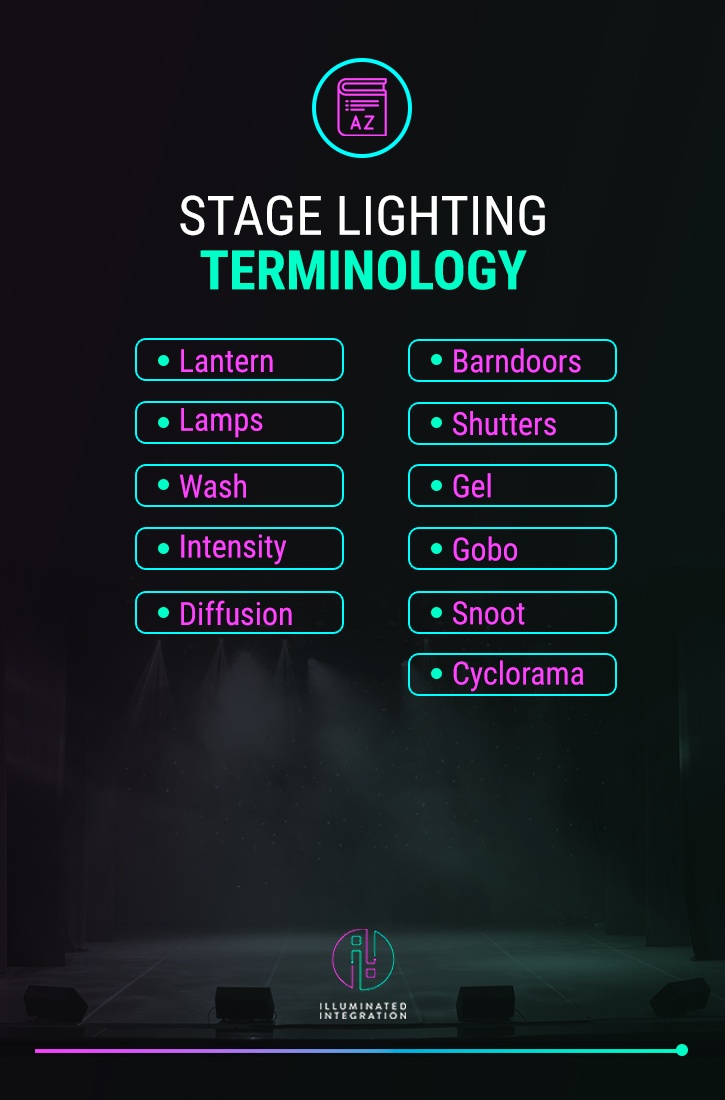

STAGE LIGHTING TERMINOLOGY

To better understand the topic of stage lighting, it helps to familiarize yourself with some stage lighting names for items and concepts that commonly come up in this field:

Lantern: Though you may simply hear them referred to as lights or lighting fixtures, the lighting units used in stage lighting are also commonly called lanterns. In Europe, the more common term is luminaire.

Lamps: Lamp is the correct term for what you may call a light bulb in a domestic lighting context. In stage lighting, the bulbs that go into light fixtures are consistently called lamps.

Wash: A wash, also known as a fill, is a wide swath of lighting that provides consistent coverage across a stage. Floodlights are typically used to create a wash.

Intensity: Intensity is the term lighting professionals use to describe a stage light’s level of brightness. A more intense light will draw more electrical power. Decreasing the electrical supply causes the light to become dimmer, or lower in intensity.

Diffusion: Diffusion is the process of dispersing light to soften it. A diffused light is the opposite of an intense beam with hard edges. Lighting engineers can use diffusion material, which is like a colorless gel, to soften the light.

Barndoors: Barndoors are sets of either two or four metal flaps that affix to the front of a stage light to cast a widespread, soft beam of light. The barndoors shape the light and create a harder edge where the light stops so the beam won’t illuminate areas you would prefer to remain dark.

Shutters: Shutters are similar to barndoors, but they are built into ellipsoidal lighting fixtures. By moving the shutters, you can manipulate the shape of the light and block certain areas.

Gel: A gel, also called a color filter, is what lighting professionals use to change the color of a beam of light. Gels consist of clear sheets with a translucent colored sheet of plastic in the middle. By sliding different gels into the color frame on a light, you can use the same light to cast many different colors.

Gobo: A gobo, also called a pattern, is a thin metal disc with a pattern cut out, like a stencil. By placing the gobo in a holder in front of a light source, the light will cast a pattern on the stage. This pattern could create an image, like a city skyline, or it could simply add some texture to the light.

Snoot: A snoot, also nicknamed a top hat after its appearance, is an opaque, cylindrical accessory you can place over a light to reduce flare or stray light that can come from lighting fixtures.

Cyclorama: A cyclorama, or a “cyc” for short, is a large cloth backdrop used on a stage. It’s typically concave, stretching in an arc from one side of the stage to the other. You can use lighting equipment to project light or images onto the cyclorama.

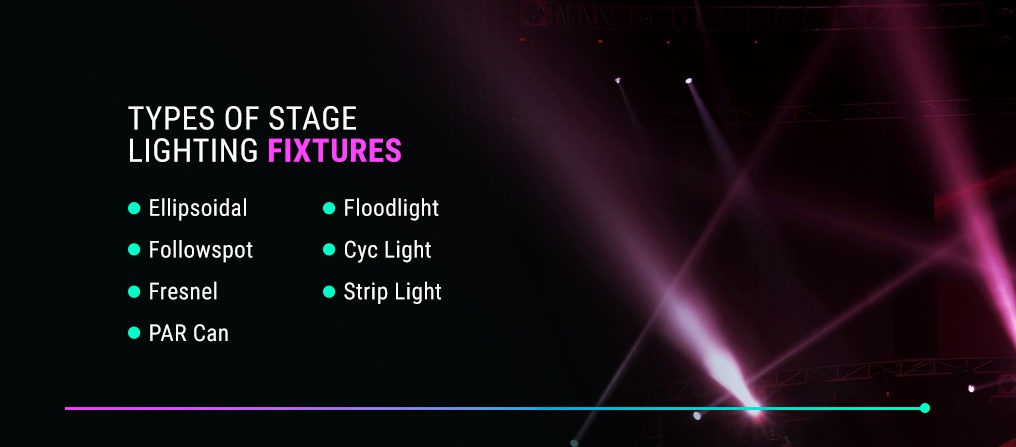

TYPES OF STAGE LIGHTING FIXTURES

There are several types of lighting fixtures that are common in stage lighting design. Each type is designed for a unique purpose, so most stage lighting setups will include multiple types of lanterns. These fixtures may include:

1. Ellipsoidal

An ellipsoidal reflector spotlight produces an intense, well-defined beam of light that is perfect for front lighting. You can adjust the focus with soft or sharp edges, use shutters to adjust the shape of the lighting and keep the light from bleeding into areas you want to remain dark. These lights can also hold gobos and gels so you can create patterns and colors with them.

2. Followspot

A followspot is a type of spotlight, so it casts an intense, focused beam of light to give extra focus to a performer moving around onstage. These lights are especially useful when you aren’t sure what path a performer will take and need to respond in real time since they are traditionally operated manually. In addition to adjusting the positioning of the followspot, the operator can also adjust the size and the intensity level of the beam, and they can easily adjust the color with built-in panels.

3. Fresnel

These lights are named after their inventor, Augustin Fresnel. What makes these lights unique is that they have a lens made of concentric rings. The light is brightest at the center ring and softens the closer it gets to the edges. These lights are a good choice for washes, though they can also produce more narrow beams of light with a soft edge. You cannot use shutters or patterns on these lights.

4. PAR Can

A parabolic aluminized reflector (PAR) can is a staple in stage lighting. PAR cans are sealed-beam lamps in cylindrical metal casings. These lights are similar to vehicle headlights and are simplistic in their design. They don’t give you precision with focus or zoom options, but you can adjust them to create horizontal or vertical beams. You can choose from standard and LED options and can use gels to create colored lights.

5. Floodlight

A floodlight is a large fixture that an operator can move horizontally or tilt vertically. They don’t have any lenses, so floodlights are determined solely by the reflector and lamp type. In symmetrical floodlights, light is distributed equally above and below the horizontal axis of the lamp. In asymmetrical floodlights, the light spreads much further in one direction than the other in the horizontal axis. Like PAR cans, floodlights cannot support patterns, beam adjustments or other accessories besides color gels and diffusion.

6. Cyc Light

Remember that a “cyc” is a large cloth backdrop. Accordingly, a cyc light is an open-faced fixture that gives an even wash of light over a cyc or another type of vertical surface. These lights can be positioned on the floor or hung close to the backdrop so they can effectively cover the backdrop in a sheet of light.

7. Strip Light

Strip lights can also be used as cyc lights, but these lights are wider than most cyc lights. They consist of multiple lamps arranged in a horizontal row. A strip light is what many lighting engineers use to add a large amount of color coverage to a stage. They can also allow you to mix colors. These lights come in both standard and LED varieties.

LIGHTING POSITIONS

One of the foundational stage lighting concepts to understand is lighting positions. The main stage lighting positions that lighting designers factor into their designs include:

Front lights: Front lights are the primary source of lighting for a performance. In many situations, you’ll use front lighting to provide a wash for the whole stage. Fixtures that point forward toward performers’ faces are an important starting point, but by themselves, they will make a performer appear flat.

Backlighting: To give a more dimensional appearance where the actor pops from the background, you also need backlighting and downlighting. Backlights are positioned toward the back of the stage, behind the performers. You can position backlights at different points vertically. PAR can fixtures work especially well for backlighting. You can change the color and intensity to customize the look.

Downlighting: Another way to add dimension to stage lighting is with downlighting. Downlighting can vary in intensity. Note that some designers use the term “downlighting” to mean lights that are positioned at the feet and cast light upwards, and others use the term to mean lights that are positioned above the stage and shine straight down or down at an angle.

Side and high side lighting: You also need lights positioned at the horizontal edges of the stage to illuminate performers from either side. High side lighting refers specifically to side lighting that is positioned high so it shines on performers’ heads and shoulders. These lights are critical for making actors’ facial expressions clearly visible.

LIGHTING COLORS AND TEXTURES

With the tools of color and texture at their disposal, lighting designers can heavily influence the visuals and atmosphere of a production. As we’ve seen, gels allow lighting technicians to change the color of lights. They can even layer or combine gels to create color variations. In using different colored lights to illuminate a scene, lighting designers may take one of these approaches:

Monochromatic: A monochromatic color scheme is limited to different shades of the same color. This is a good choice when you want to keep the lighting simple or emphasize one color.

Complementary: Complementary colors are opposite of each other on the color wheel. Pairing these opposites together is a good way to create contrast. For example, you could pair blue and yellow or red and green. You shouldn’t layer complementary colors because they will create muddy hues.

Triads: Lighting designers can use three different colors in a scene for more visual variety. When these colors create a triangle on the color wheel, the color scheme is known as a triad. For example, you could combine red, green and blue or cyan, magenta and yellow.

Adjacent colors: By pairing adjacent colors — that is, colors next to each other on the color wheel — a lighting designer can create a faded look from one color to the next.

Cool or warm colors: You can also invoke a certain mood and color theme by combining colors of the same temperature. For example, combining red, orange and yellow can make the scene feel warm.

Colored lighting can invoke a certain mood or contribute to the overall feel of a scene, but that’s not all. Changes in the lighting’s color scheme can also act symbolically and be associated with certain themes or characters in a show. For example, a lighting designer for a production of “Swan Lake” noted in an interview that, while the show’s color palette is mostly white, the lighting incorporates a bit of blue when the Swan is onstage.

Texture is another important way lighting designers can directly impact the visuals in a scene. By using gobos with patterns on them, lighting designers can transform the look of a scene. Even in productions where sets are minimal, the right lighting pattern can create the impression that the performers are in a jungle, in the city, outside on a starry night or in a church with a stained glass window.

DIVIDING THE STAGE

At this point, you may be wondering how lighting designers plan the lighting for a stage production. This is an involved process that starts with reading the script and extends all the way to the live performance. After familiarizing themselves with the production — in terms of the characters, plot and the set that will be onstage — a lighting designer can begin to develop a plan.

This plan will start with dividing the stage into areas that require independent lighting control. For productions that use the whole stage for most scenes, the lighting designer will designate general segments that are evenly divided across the stage. The simplest example would be a center segment with a side segment on stage left and stage right.

For productions with more segmented sets and scenes that take place at different parts of the stage, there will be more definitive, natural area designations for the lighting designer to start with. For instance, there may be a spot on the stage where a narrator appears periodically to speak or where a soloist will stand to perform during an orchestra concert. You would want this spot to be its own area.

The way a designer designates areas will entirely depend on the production and the set, so there is no one-size-fits-all approach. Each new production a lighting designer works on must start from the ground up.

After the designer divides the stage by area, they will think about each area in terms of color. Do certain areas need to have their own controllable variations in color? In some cases, you may be able to group adjacent segments on the stage. Or you may need each segment to have its own color controls.

In the early stages of their design, lighting professionals tend to think generally about color in terms of warm, cool and neutral lighting. They can also begin to think more specifically about individual colors if they know their colors will differ decidedly from area to area on the stage.

HANGING LIGHT FIXTURES

Installing light fixtures is a task best left to a trusted professional who has the necessary equipment and expertise in how to hang stage lights. The most important thing to prioritize is safety. Professional lighting installers will typically attach lanterns to a steel pipe or truss using lighting clamps. As installers connect the lights to the pipe or truss, they will also use a safety cable, which wraps around both the truss and the yoke or handle of the fixture, to secure it further.

All the cabling for lighting should be run overhead whenever possible. Some pipes, called internally-wired bars (IWBs), are equipped with sockets so you can power your lights in a simpler fashion. When cable needs to run across the floor, it’s best to create a recessed track for the cable so it isn’t a tripping hazard or an obstacle for moving sets.

The positioning of lights depends on the way the designer has segmented the stage and the stage lighting angles they want to achieve. There will likely be several groupings of lights surrounding the stage. Note that some lights, like a followspot, aren’t hung at all. They are freestanding and may be positioned in a variety of points within the theater or arena.

HOW TO WORK WITH A LIGHTING DESIGNER

As an experienced lighting designer and professor of lighting design points out, there is no exact formula for the lighting design process or who collaborates on a production because each production is unique. Lighting designers are the experts when it comes to lighting up a stage, but directors or others working on a production can assist the lighting designer so they can do their absolute best. Follow these tips when working with a stage lighting designer:

Start early: Start communicating with your lighting designer early in the process. This means sharing a script, a video of the show or whatever materials you can to help them understand the content of the production. Lighting design takes time, so don’t wait until you’re in the late stages of rehearsals to begin working with a lighting designer.

Communicate your goals and preferences: If the writer, choreographer, director or composer knows there are certain artistic goals they want to achieve with the lighting, communicate these goals. These could be overarching goals for the lighting, or they could be specific. For example, you may discuss a color shift that should happen during a scene. Ensure that if you have certain things you’re looking for in the lighting, you let your designer know so they can take these preferences into account.

Give them artistic freedom: While you do want to offer your own goals for consideration, it’s important to give your lighting designer enough leeway to truly design the lighting for the show. Professional lighting designers are likely to have creative insights and technical expertise you don’t have, and they can leverage this specialized knowledge to create something extraordinary.